|

Abstract: |

Background of bar codes on packages

The Dutch Association of Hospital Pharmacists (NVZA) has recommended that all deliverable medications should be formulated in unit-dose cells (EAGs).

It is vital that all EAGs contain an identifying bar code. This will provide a registerable electronic guarantee that the right medication has been given to the right patient [1].

EAGs are single unit packages of varying formulations, e.g. oral tablets or capsules; liquid-containing ampoules, syringes, or vials; ointments, etc. EAGs are normally labelled with the following information:

- non-proprietary and proprietary names

- dosage form

- strength

- expiration date

- control number (lot number)

- bar code that has a unique number called a GTIN (global trade item number).

The inclusion of a bar code is vital. European Association of Hospital Pharmacists (EAHP) [2] and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) [3] have recommended that unit-dose formulations are available for every hospital-administered drug, and that these drugs should have identifying bar codes.

To better understand the necessity for an identifying bar code, a short explanation of the processes involved are now discussed.

Prescription to administration

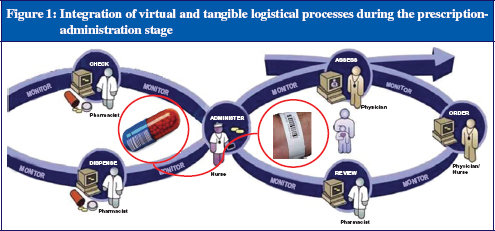

In the prescription-administration process there are two kinds of logistic: the virtual logistic, i.e. the process involved with the ordering of the medication; and the tangible logistic, i.e. the process involved when the drug is administered to the patient, see Figure 1.

These two logistical processes come together when the nurse is administering the drug to the patient. At that moment, the patient, the medication and the information about the patient’s prescription must be matched, not only visually by the nurse, but also by the electronic bar code identification system. To satisfy this process, a few solutions have been introduced. These will be discussed in the remainder of this article.

Cabinets

Cabinets are computerised ward stocks connected to the pharmacy-system/CPOE-system. The cabinet only allows the medication to be available to the nurse at the time of administration. These machines are always up to date and can handle all packaging. However, they can be located quite a distance away from the patient, meaning that the administration check–medication overview–cannot be reviewed in the patient’s presence. In addition, when a medication is not packaged in unit doses, the nurse is sometimes required to administer multiple doses of the same medication at the same time. This could lead to mix-ups. From a financial perspective, the total cost of ownership of the cabinets is relatively high, but the handling costs are relatively low.

Patient-specific logistics, manual

In this system, the medication is made patient-specific by putting it in a patient-drawer in a mobile cart. This is done by either the pharmacy department or the nurses. A paper form of the medication overview is available on the cart. The system is able to handle all packaging, and providing it is labelled correctly the nurse is able to check the medication. However, preparation of the cart is time-intensive, and errors can be made, particularly if staff are inexperienced or inadequately trained. The total cost of ownership of a cart is low, the handling costs are high.

Patient specific logistics, using FDS

The medication is made patient-specific in the pharmacy by an FDS machine which places the medication in a small plastic bag labelled with patient identification and medication content. The major problem with this method is that when more than one tablet is bagged, a change in medication (stop or dose change) cannot be managed by the nurse because the different tablets are unidentifiable. If tablets are packed one by one, this method is very expensive, as additional packaging materials and ink ribbons are costly. Only tablets and capsules are supported in most FDS systems, although separate FDS systems are available which can distribute ampoules and infusion bags. The total cost of ownership of the cabinets is relatively high, the handling costs are relatively low.

Patient specific logistics, using BAP

A solution that is flexible and safe is a cabinet-like solution which is on wheels and allows adequately bar-coded medication to be brought directly to the patients’ bed. In The Netherlands, such apparatus is known as a BAP-cart, (bed-side assortment picking). This apparatus is able to handle all types of packaging, but requires an adequately identifiable (preferably bar-coded) cell package. The total cost of ownership of the carts is relatively low, the handling costs are also low.

Prescription to preparation for injection/infusion

Having adequate packaging and labelling is also crucial during the preparation of parenteral medication. Although most preparations in The Netherlands are made on the ward by the nurse, there is an increasing awareness that preparing these medications in the pharmacy would be more beneficial. This will help to avoid mix-ups, which would be difficult to detect at a later stage. Compared to medications that are synthesised on the ward, pharmacy-prepared medications are synthesised under more aseptic conditions. This would usually mean that a second person is required to check the identification and amounts of compound used. However, when an identifying bar code is present on each compound, the control could be efficiently performed using an electronic bar code scanner, computer software, and a mechanical scale.

Current status

To date, there has been little progress in creating a uniform identifying bar code system on primary packaging.

One of the reasons that the pharmaceutical industry has not adjusted their packaging to the standard requested by FDA, ASHP, EAHP (and NVZA), may be that each market has different requirements, e.g. the product identification number. This would make any individual packaging updates costly.

Another issue for the pharmaceutical industry is the space required for a bar code on a small unit-dose package. This problem is also recognised by FDA, ‘The pertinent labelling regulations present problems in interpretation in that they are inconsistent with respect to exemptions for containers too small or otherwise unable to accommodate a label with sufficient space to bear all mandatory information. As a result of several recent regulatory actions emphasizing these inconsistencies, the regulations will be rewritten in the future to clarify the requirements’ [4].

These issues combined with a lacking sense of urgency in the hospitals mean that stakeholders are still waiting for developments. Some hospitals developed workarounds, e.g. in-house re-labelling of the medication, but these actions generally proved problematic. Some industries print a bar code on their primary package, but the presence of an identifying bar code is still rare.

Hopefully the following developments can make the difference:

- GS1 has developed a global standard for identifying medication on each possible level of packaging. The pharmaceutical industry is urged to comply with this standard. The interest of the industry for a global identification number is that it has cost-saving potential in B2B logistics and helps to avoid counterfeit. A new two-dimensional way of presenting a bar code has become possible where the limited amount of space on the cell is no longer an issue. This makes it possible to have one primary package for each product for (almost) the entire world.

- Patient safety is a rising topic in the boardroom of hospitals and pharmaceutical companies.

Conclusion

It should be possible to develop a type of packaging which is user-friendly to hospital staff, enhances patient safety, and provides sufficient incentive to the industry to develop it. With this in mind, the NVZA has initiated dialogue with the pharmaceutical industry to address and discuss this issue and promote EAG packing.

We recommend that for all levels of packaging including EAGs, industry should:

- obtain GTINs

- print GTINs on their product bar codes

- include Lot numbers and expiry dates

- produce labels which are uniform in layout.

Author

Bas Drese

Hospital Pharmacist

Gelre Ziekenhuizen

31 Albert Schweitzerlaan

NL-7334 DZ Apeldoorn Zuidwest, The Netherlands

References

1. De Nederlandse Vereniging van Ziekenhuisapothekers. EAG standpunt NVZA [homepage on the Internet]. 2009 [cited 2012 Feb 20]. Dutch. Available from: www.2nvza.nl/layout/raadplegen.asp?display=2&atoom=13118&atoomsrt=2&actie=2

2. European Association of Hospital Pharmacists. Bar coded unit doses [homepage on the Internet]. 2006 [cited 2012 Feb 20]. Available from: www.eahp.eu/Advocacy/Bar-coded-unit-doses

3. American Society of Health-system Pharmacists. ASHP statement on bar-code verification during inventory, preparation, and dispensing of medications. Am J Health-Syst Pharm. 2011;68:442-5.

4. US Food and Drug Administration. Inspections, compliance, enforcement, and criminal investigations – CPG Sec 430.100 Unit dose labeling for solid and liquid oral dosage forms [homepage on the Internet]. 1984 [updated 2010 Jan 20; cited 2012 Feb 20]. Available from: www.fda.gov/ICECI/ComplianceManuals/CompliancePolicyGuidanceManual/ucm074377.htm